T he Next Big Thing is dead. Long live the Next Big Thing. Few phrases better capture the anticipation, intrigue, and magic of tech innovation. The phrase has been an apt descriptor for such standouts as the market-ready product that quickly revolutionizes the tech landscape (think first smartphone release). Increasingly, though, that phenomena is less relevant in a world defined not by ‘one big thing,’ but rather, the iterative fusion of technology building blocks coupled with a generous helping of people and process. This may entail the stacking of foundational infrastructure and enabling components with emerging general-purpose technologies, such as AI, and then rounded out with data, an ‘as-a-service’ user experience, and business process optimization. The implications are both exciting – the ingredients of innovation have never been more accessible, and trying, as users and technology providers work to understand an ever-growing set of building blocks and how the pieces fit to drive digital transformation. Against this backdrop, CompTIA explores the forces shaping the information technology industry, its workforce, and its business models in the year ahead.

There have been many labels for the most recent waves of technology that are redefining business and society, and one of these labels is the “Fourth Industrial Revolution.” This suggests not only a drastic change in the way work is done, but a new foundational infrastructure that enables that work. Just as previous eras of industry were driven by the creation of railroads, telephone networks and power grids, the modern digital economy rests on a foundation built in three parts. First is cloud computing, a model that brings greater flexibility and control to IT activities. Second is edge computing, which extends the principles of cloud computing from a centralized location to the places where data is being captured. Finally, 5G networks provide fast and robust connections between each node. Each one of these areas on its own provides opportunity for a company to innovate; taken together, they signal a new way of thinking about IT applications. Today, most businesses likely have the greatest amount of experience with cloud computing, but that experience has still been centered around porting existing applications to a cloud provider. True transformation starts with rebuilding applications to take advantage of cloud computing’s unique properties, and this transformation will accelerate as those applications also factor in the location awareness of edge computing and the dynamic capabilities of 5G networking. Fully evolved applications will be the mechanisms for new economic activity, and IT skills will likewise evolve to support the new structure.

For most people, the changes taking place in IT infrastructure will happen behind the scenes, but there will be changes in the front-end experience as well. With mobile devices and cellular networks, there has already been a shift in the perception of where computing takes place. It is no longer confined to an office or home, but is increasingly viewed as something that can be done from any location. Even so, there is still a strong tie to a computing device. As the Internet of Things continues to grow, every imaginable object will have the potential to be a computing device, collecting data and providing new capabilities. With the wide spread of computing power, artificial intelligence will automate tasks to reduce complexity and scan the environment to understand context. The net result will be ambient computing, with activity that was once confined to a device now taking place seamlessly with minimal user interaction. For example, think of smart lighting. The first iteration of smart lighting is lighting that is connected to the Internet and can be controlled through an app. The second iteration involves manually building some sort of automation. With ambient computing, smart lighting will automate itself, recognizing when devices enter a room or operating on a schedule built through pattern recognition. This will drive behavior change, as end users can take advantage of new efficiencies but must also be aware of nasty side effects related to security or privacy. In building out new digital experiences, IT professionals and solution providers will need to think carefully about user behavior, considering new interfaces and mitigating potential downsides. The new behavior on the front end along with the substantial changes on the back end will jointly drive big change in IT support, which will continue to move from tactical maintenance to strategic enablement.

The past year has not been especially kind to blockchain and other distributed ledger technologies (DLT). Cryptocurrency values have fallen precipitously, and killer apps have not yet emerged. Other types of distributed technology, such as distributed databases or the Tor browser, leverage distributed networks to extend established architectural concepts. DLT takes things a step further, introducing an entirely new architectural approach made possible by distributed networks and cryptography. In theory, DLT provides an improved method for recording many types of digital transactions. In practice, the question remains whether those improvements will be significant enough to unseat established models. Most of the DLT focus remains on the financial sector, where a typical pattern for disruptive technology is playing out. In markets with solid financial structures, the technology is attempting to disrupt well-established mechanisms. In markets where the financial infrastructure is less stable, DLT provides a solution where none existed before. This pattern can be extended to other applications as well, and it is difficult to tell where DLT is most likely to shake things up. Certainly, there is the potential for DLT to become part of the modern digital infrastructure, where the primary value is not the ledger technology itself but the distributed apps that can be built on top. To reach this point, though, there will need to be further breakthroughs in certain aspects, such as transactional speed or the method for building consensus. IT pros and solution providers should certainly remain aware of DLT as they are keeping up with a wide range of emerging trends, although long-term there may only be targeted instances where deep skills are needed, as with other enabling technologies. DLT quickly stepped in to the spotlight as a revolutionary technology, and the coming year will continue to see a high level of activity even with the inevitable backlash that comes at this point in the hype cycle.

The concept of “stacks” is a common convention in describing how Lego-like building blocks come together to form a whole. Software stacks, such as LAMP or MEAN, or, skillsets, such as full stack developer or CompTIA Security Infrastructure Expert (CISE), often come to mind. Taking this idea one step further yields what can be characterized as stackable technologies. As the name implies, stackable technologies allow organizations to piece together components to meet an end goal. While this is not necessarily a new concept, advances in a number of areas, from API-enabled cloud platforms and containers, to modular hardware design and business process widgets, facilitate more sophisticated and more efficient stacking of technologies. This, of course, leads to greater levels of digitization and business transformation. For example, it may entail stacking technologies in a given sector, such as agtech, where drones-as-a-service may incorporate elements of hardware, computer vision, IoT, and analytics to automate crop maintenance. Or, stacking may help a business provide a more engaging and seamless customer experience through combinations of mobile pay, AR, and virtual agents. For CIOs, business leaders, or technology partners, this will mean an even greater need to connect the dots across a broad set of existing and emerging technologies.

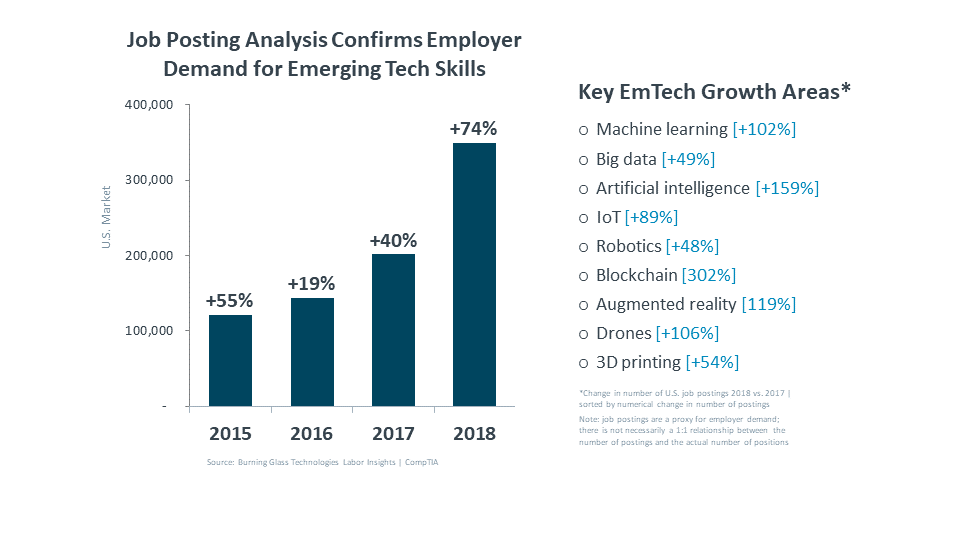

Blockchain, AI, VR, IoT, drones. Those are but a few of the newer technologies bursting onto the scene, promising to shake up how businesses and consumers navigate their way through innumerable aspects of life and work. For the channel, how much is hype vs. reality? A little of both right now, truth be told, but in 2019 more reality and less hype will come to fore for all players in the business of emerging tech. (See Appendix for definitions, sizing, and additional information covering the information technology channel). There are really two main things for channel firms today to consider: which emerging techs fit into their business best and what resources and training are needed to ramp up technical and sales staff to effectively integrate these new wares into the business. Clearly, these are typical challenges associated with adding any new solution or skill to a portfolio, but with emerging tech categories there are some new wrinkles to consider. Many of these solutions are more akin to enabling technologies than products in their own right. Consider something like artificial intelligence. AI is often a feature baked into other products, solutions, Web sites, etc. Not being standalone, AI is a component that channel practitioners will need to weave into what they ultimately sell. A challenge, yes; but also, an opportunity. An emerging tech like AI could very well be the value-add or differentiator that closes the deal with a customer when woven into a product or solution. Working closely with emerging technologies also could lead to more channel firms developing their own intellectual property, such as custom coding to build a new solution based on an emerging tech component, a trend that CompTIA has examined over the past few years. Given these opportunities, many channel practitioners will be exiting their emerging-tech experimental phase in 2019 to move into full adoption with an eye on revenue-generation.

Today’s customers are more tech-savvy, more diverse, and more finicky than ever. From desiring seamless customer service to demanding myriad digital options for commerce, many buyers are no longer just looking for the right product, but also seeking a satisfying experience in attaining it. Apple and Amazon have been providing this for years, but it’s also a growing imperative across the IT channel, where improving customer interactions is a pathway to getting ahead. Savvy channel firms are placing more priority on how they engage digitally with customers across various platforms, how they provide customer service creatively with the most cutting-edge tools, and how they innovate their own business internally. Top of mind for the upcoming year is the idea of getting even closer to the customer. Forty-six percent of respondents in the CompTIA IT Industry Outlook 2019 study say they plan to focus on personalization in 2019. This involves tailoring experiences, content and engagement strategies to individual customer preferences. The catch word is “hyper-personalization.” This model takes the time-honored concept of segmenting your customers into specific buckets (small, medium or large-sized, for example) to the extreme. It brings marketing and engagement down to the individual level. Already widely used in the retail and content marketing industries today, hyper-personalization in the year ahead can become a differentiator for many channel firms. Data analytics reside at the heart of this approach. By using data analytics, and increasingly artificial intelligence tools, companies can provide highly personalized messaging/marketing, product/service offerings, delivery and implementation options etc. directly to that customer. Research study after research study finds that the more tailored the message, the more likely the consumer will bite.

Partner-to-partner (P2P) collaboration has always been a bit of holy grail in the channel. A way to fill skills gaps, a way to present a more comprehensive front to customers, a way to be bigger than you are. And yet for all the hype and promise, many channel-firm-to-channel-firm partnerships simply have not worked. What began as a handshake agreement to do one joint deal later fizzled when the parties skipped the due diligence needed to keep the partnerships alive. Vibrant partnerships require more than a handshake. They need to be formalized by the two parties, with specific duties, roles and accountability outlined. And then they need to be nurtured through regular communications. Looking ahead to today, there is renewed optimism about partnerships, due in large part to the expanding ecosystem of new channel players from the SaaS world eager to pair up with traditional infrastructure practitioners. In an increasingly applications-centric world, infrastructure companies that comprise the older base of the channel are needing to fill skills gaps in software to appeal to customers. Likewise, newer SaaS firms often lack hardware, networking, and security acumen. Short of hiring new staff and taking on new disciplines, partnerships are a good idea. Nearly two thirds of infrastructure channel firms reported partnering in the last year with a SaaS company, ISV, or vertical industry applications specialist, according to CompTIA’s 7th State of the Channel research. Of that group, nearly 6 in 10 said they have had a positive experience doing so. The benefits, they contend, are expanded business opportunities and narrowed skills gaps, especially in certain technology disciplines like data analytics where a lack of skill has held the channel back from penetrating enterprise accounts. These partnerships are not exclusive to SaaS and other software providers. Today, non-core technology entities such as law firms, accounting firms, digital marketers, consultants, and even consumer goods companies (think P&G, IKEA, Kohler…) are offering or influencing tech services as well. While clearly these new entrants could be seen as competitors, they also could help traditional solution providers gain a foothold into vertical-industry specialization.

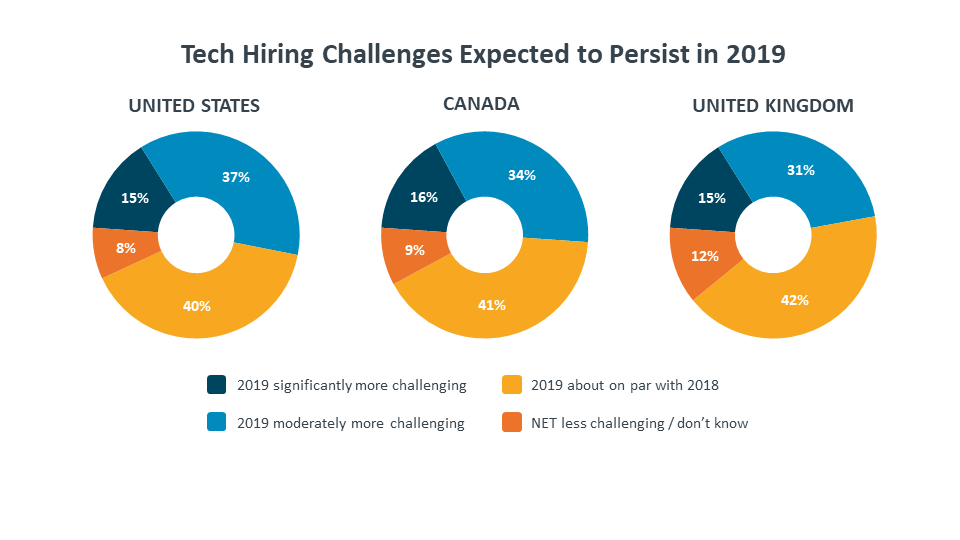

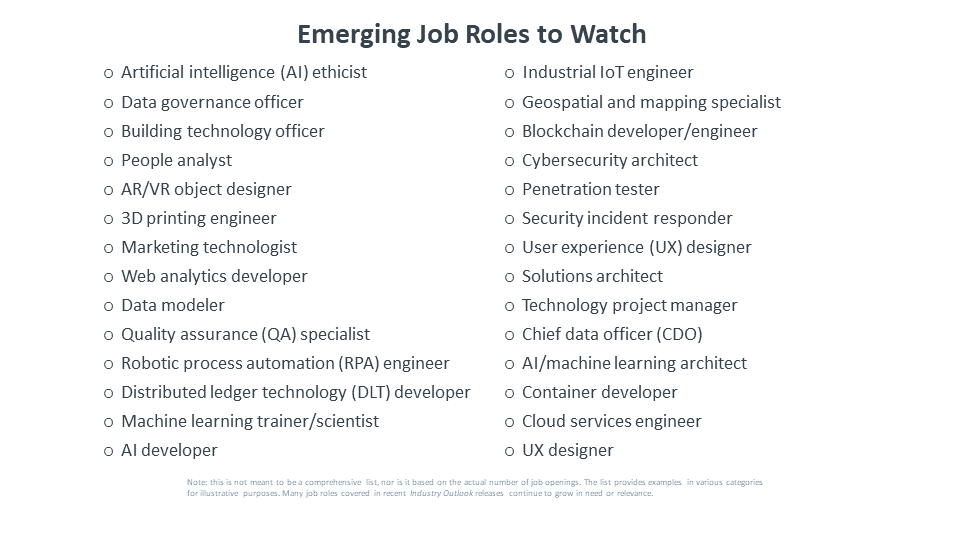

No surprise, the IT industry’s tight labor market and tech skills gap challenges continue unabated. In fact, it’s not just a problem for the technology industry, but one that is affecting most every industry in the economy. Consider that the U.S. unemployment rate for IT occupations stands at approximately 2.1 percent, nearly half the national unemployment rate (a pattern that holds for many countries and regions of the world). If you have job openings at your company, especially for disciplines around emerging technologies, data analytics, application development and the like, finding and retaining workers has likely been tough-going (see Tech Workforce section of this report). But while the tech-labor shortage remains a challenge, it also has sparked some creative thinking. Take tech giants Apple, Google and IBM, for example. These companies no longer require a four-year college degree for many of their positions, including those in some technical roles. Loosening up this age-old requirement opens the doors for thousands of potential hires. And it is recognition that many of the skills required for a career in tech can be acquired via alternatives to the four-year academic path. There’s self-learning, community college enrollment, and on-the-job training, among other valuable routes to a career in tech. Case in point: many employers have stepped up efforts to help existing employees pursue IT certifications and other professional development credentials as a way to offset the lack of external candidates for jobs in newer skills areas. Other companies have put their weight behind “knowledge-sharing” or mentoring programs that are less formal than classroom retraining. Lunch-and-learns conducted by older employees to newer ones are one example. The practice of having Gen Y and Gen Z-age workers create videos about new technologies, tools and approaches is also gaining in popularity within organizations. Likewise, using online outlets such as YouTube and customized podcasts is another means of providing workers avenues to retrain in a self-paced fashion. These approaches are especially critical to channel partners contending with aging workforces. Relatedly, experimentation with the traditional apprenticeship model is seeking to provide new avenues for young people and employers to develop the right mix of hard skills, soft skills, and on-the-job experience. Lastly, it shouldn’t take a tight labor market to prompt tech companies to review their approaches to expanding the pipeline to boost the numbers of those under-represented in the industry. While there are positive examples of efforts to increase gender and ethnic diversity, there is still much work to be done.

While the dire warnings of “the robots are coming for our jobs” tend to draw the headlines, the reality of the situation is far more nuanced. Automating technologies has undoubtedly displaced segments of workers through substitution. This represents one end of the human-technology continuum; with the other end being workers using tools where technology plays a passive role (think email or traditional spreadsheets). Between these two endpoints sits a hybrid model whereby humans leverage and act on technology; and intelligent technology proactively does the same to workers. The underlying assumption with this model is the recognition that humans and intelligent technologies will always have strengths and weaknesses, much like any team. In practice, these digital-human models may take many forms. In industrial settings, collaboration robots (co-bot) may work hand-in-hand with humans, both responding to instructions, but also acting independently based on stimuli and objective. Across just about every knowledge worker occupation (e.g. physicians, sales reps, teachers, accountants, project managers etc.), the potential exists to deploy intelligent technologies to take on mundane tasks, and increasingly higher-level functions, such as predictive modeling, scenario analysis, or even serving as a type of personal coach. The consultancy McKinsey & Company estimates 6 in 10 occupations – among over 800 evaluated, have at least 30% of their job tasks that could potentially be automated, which points to the far-reaching impact of digital-human work models. This will, of course, require ongoing trial and error to optimize work processes, as well as investments in training for both workers and machines.

From the global economy to everyday activities, technology is changing the world. However, for those working in technology, this is not a chance to simply claim victory and reap rewards. Changes at the scale made possible by technology will inevitably cause ripple effects. Those effects have been coming to light over the past year, from security and privacy incidents to AI bias to technology that is not quite ready for prime time. A negative perception of the technology industry could lead to many different scenarios, from increased government regulation to lower customer confidence. The answer is not to place barriers in the way of technical progress, but to responsibly take action that allows continued growth while accounting for potential missteps. The business of technology has typically focused on individual solutions: hardware for IT operations or applications that serve a specific business purpose. As there is a shift to a broader system mindset, there is the opportunity—and the obligation—to consider the full extent of the system being implemented. Hardware choices are not just about productivity and cost; they are also about environmental impact. Data management is not just about storage and analytics; it is also about privacy and transparency. While these big-picture issues have typically been the concern of a CIO, everyday technology professionals will now be expanding their expertise from hard-core technical skills to include cross-departmental collaboration and strategic business thinking. This broader skill set will allow tech pros to drive conversations around unintended consequences. In today’s landscape, technology may sometimes be cast in a negative light, but the tech industry itself will learn from the past and set the course for a prosperous and conscientious future.

In simplest terms, an algorithm can be described as a set of instructions. Algorithms can be as basic as an ‘if then’ statement and as mind-blowing as artificial intelligence (AI) teaching itself to develop its own algorithms to solve complex problems (see examples of AI spawning its own AI ‘child’). Algorithms handle everything from what users see in their social media feed to content recommendations on Netflix to optimizing the delivery route of UPS drivers to making medicine smarter. Algorithms are often the “secret sauce” of applications, business processes, and customer experiences (CX). But what happens when the algorithms, and increasingly the AI behind them, make decisions that are questionable, or flat out wrong? Algorithmic bias has made its way into the headlines with examples of experimental systems for hiring or screening that scour a candidate’s data footprint and then draw conclusions about a person’s attitude and disposition. Or, consider the social credit system the Chinese government is piloting. Similar to a credit rating score, the algorithmic system rewards behaviors considered positive, and punishes citizens with low scores for behaviors considered negative, such as bad driving, smoking in the wrong place, or spending too much time playing videogames (the consequences of a low score are real: reports indicate millions of people have been blocked from buying tickets for air travel as punishment). As these systems become more ubiquitous; industry, government, and society will face increasingly thorny questions over the tradeoffs between innovation and the issues of transparency, explainability, and accountability.

The digital transformation of “low tech” encompasses a number of interrelated sub-trends. The Moore’s Law effect of more powerful sensors and components at ever-lower prices has contributed to the fast-growing expansion of the internet of things (IoT) footprint. Through refinements to standards and protocols, along with advances in interoperability, technologies are increasingly out-of-the-box ready to deploy, allowing for ease of experimentation. Taken together, more technology is finding its way into what could be characterized as “low tech” business activities or occupations. To clarify, low tech doesn’t necessarily mean low skill or lacking in sophistication, but rather, up until recently, there hasn’t been a need or justification for a heavy-tech presence. Sectors that fit this description may include restaurants, farming, delivery of goods, building management, and environmental management, just to name a few. More specifically, consider how sensors, data, AI, and robotics process automation (RPA) have the potential to impact the entire chain from the growing of food, to the preparation of food, to the delivery of food. On the workforce front, according to a study from the Brookings Institute on the digitalization of the workforce, occupations classified as low- or medium skill have seen a dramatic jump in the transition to digital skills. Occupations such as roofers, carpenters, landscapers, drivers, personal aides, or various types of trades and technicians, are steadily incorporating more technologies and the corresponding digital skills. With the pervasive focus on data coupled with the growth of AI and everything-as-a-service models, the rate and scope of change will likely accelerate. This does, however, raise a number of questions in the debate over the meaning of value and solving a true problem versus applying technology for technology’s sake. Potential adoption inhibitors such as resistance to change, resource constraints, digital divides, and skills gaps will factor heavily into the equation as well.

The ingredients of innovation have never been more accessible. With little more than a broadband connection and a credit card, a startup can spin up powerful, scalable compute and storage capacity with minimal investment. Add in open source code, stackable technologies, talent marketplaces, and creative financing and the ingredients are all there for innovation to flourish. The data bear this out as tech hubs have sprouted up across the globe (think Toronto, Nairobi, Budapest, Singapore, Stockholm, Dubai, and Sao Paulo, to name just a few). While Silicon Valley and other U.S. cities remain dominant players, their share of the total “innovation pie” is shrinking due to accelerating growth in markets around the world. This means the next breakthrough in fintech, smart cities, AI, robotics, quantum computing, or ‘to-be-determined’ could occur in any number of global tech hubs. Countries looking to leapfrog ahead increasingly pursue efforts to enhance their appeal, which typically starts with building the most tech-savvy workforce possible. Other efforts may revolve around support for R&D, public-private partnerships that facilitate the efficient transfer and deployment of technology, or targeted innovation policies. Lastly, factors such as livability, affordability, and openness cannot be overlooked when the competition for talent extends beyond borders. As a counterpoint, digital divides and “winner-take-all” market concentrations continue to be problematic and must be addressed to ensure long-term economic vibrancy.

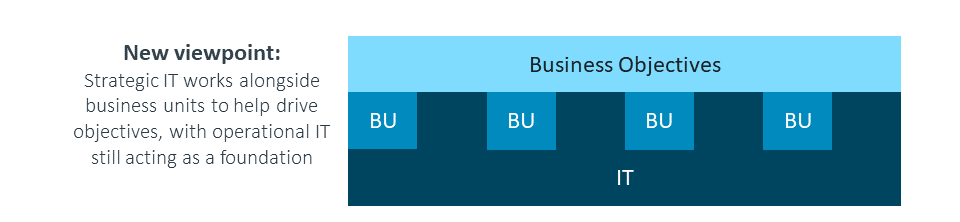

The critical difference between today’s IT and the IT of 10 or 20 years ago is the degree to which technology is being used to drive the strategic goals of a business. Certainly, there has always been some mix of tactics and strategy in the directive of any IT function, with that mix varying based on the size of the business, the vertical industry, or the attitudes of upper management. But the shift towards strategy is a general phenomenon that has affected all businesses and driven a new paradigm.

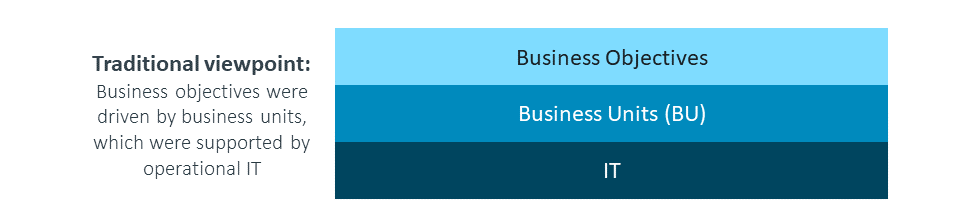

It is an oversimplification to say that IT was ever purely tactical, but that model helps illustrate the organizational perception of IT through much of its history. In this traditional viewpoint, corporate goals were considered the domain of the business units. Getting product to market and driving customer satisfaction was the purview of the sales team. Geographic expansion rested on the shoulders of the operations team. In turn, the business units relied on the IT function to provide support that allowed them to perform their jobs with greater efficiency. Constructing a technical foundation, delivering the right endpoint tools, and troubleshooting user issues were all important tasks within a company, but primarily to the extent that they drove productivity. IT was often viewed as a cost center, striving to deliver a specific level of service within the lowest budget possible.

In contrast, modern IT has expanded to more explicitly serve a dual purpose. Along with the tactical support work that continues to be a requirement, IT now has a role to play in directly driving strategic objectives. Customer acquisition happens on digital platforms. Brand awareness is built through social media. Market share is gained through omnichannel experiences. These initiatives are not achieved simply by building programs on top of technology, but by using technology as the primary mechanism for success.

Expansion into a more strategic role creates two new types of interaction for the IT team. The first is the direct connection to business objectives. This brings IT into upper-level organizational discussions, where requirements are broader and more abstract. Rather than receiving a request that has been funneled through business units and may map to an individual application, IT must consider the overall needs of the business and construct systems that address many concerns simultaneously. As an example, a traditional request may have been “the sales team needs a tool that provides more robust information on customers,” and a more current request may be “the business needs consolidated insights into our customer base so we can plan future products.”

The second new interaction is a partnering relationship with business units. In the past, the relationship was primarily one of support. Now the IT team is working alongside the business units as they build systems together or as the IT team guides technology procured by the line of business. With this activity happening at a level below the overall strategic direction, the challenge here is in building consensus around tradeoffs. This requires some communication of technical details to the business unit, and it also requires the IT team to build knowledge around line of business priorities.

Recent CompTIA research confirms the shift towards more balance between tactical IT and strategic IT. When asked about the role of technology within business, the top response is fairly traditional: “Technology enables our business processes” (43% of companies surveyed strongly agree with that statement). However, the next three responses are all broader in nature: “We are using technology to drive our business outcomes” (39% strongly agree), “The technology function plays a critical role in strategic planning” (36% strongly agree), and “We are redefining our business thanks to technology” (34% strongly agree).

Within large organizations, the images above primarily represent internal resources. But most companies in the SMB space rely on a mix of internal resources and third-party support for their IT function. The concept is the same, though—a shift towards strategic thinking drives changes not only to the structure and role of an internal IT team, but also to the nature of relationships with outside partners. These partners may be asked to support corporate goals and provide input to the planning process, which may drive companies to broaden their horizons as they consider their partner ecosystem.

It must be noted that the diagram depicting a modern view of enterprise technology is not drawn to scale. While the role of IT has expanded to include a larger strategic component, IT teams have not usually grown at the same rate. This presents a unique challenge for CIOs and other individuals responsible for technology. Without significant resource growth, they not only need to add specialized technical skills, but also need to build a new operational model.

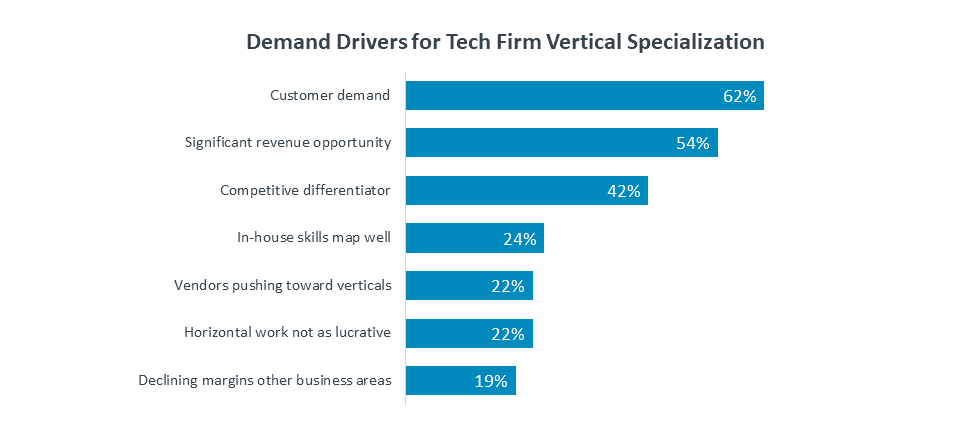

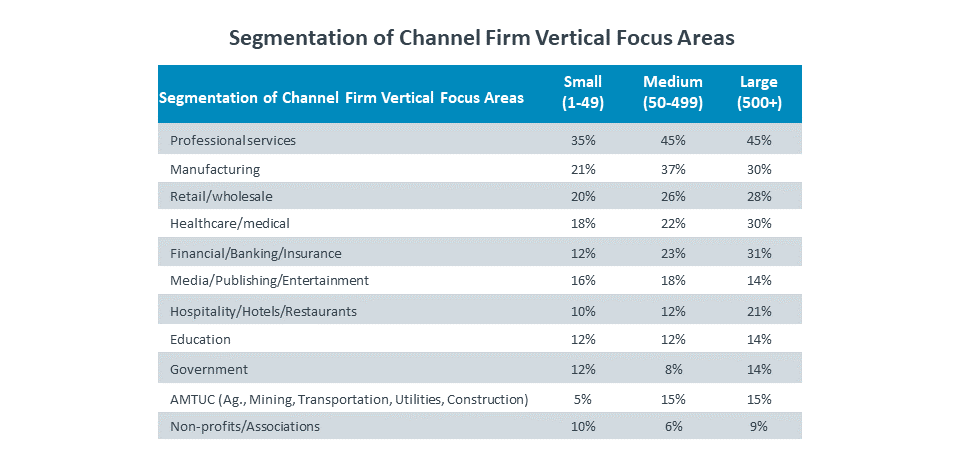

Technology is a crowded market today, leaving those in the business of tech scouting for every opportunity to differentiate themselves from the fray. This is especially true as the ranks of the channel expand to more non-traditional players that possess new sets of skills, different vendor partners and/or routes to market. One approach, though not new, is gaining steam: the pursuit of a vertical industry specialization. Focusing on a specific industry allows channel firms to move beyond horizontal solutions to become more granular in what they do; in effect, attaining know-it-all status in a niche market such as healthcare, retail, manufacturing and beyond.

Plus, customers love it. Finally, their tech providers are speaking their specific business language. That language, at its core, flows from applications’ expertise, which is key to a vertical specialty. Most basic infrastructure engagements – devices, networking, security and other hardware – are repeatable; it’s the same sales and implementation process whether you are dealing with a small doctor’s office, a car dealership or a manufacturing plant. But with verticals, it is about understanding the software, all of those specific-use applications that pertain to the industry in question. That will earn you true vertical street cred.

Applications-specific vertical expertise fits well in today’s cloud-based software world. Many cloud-based ISVs are developing discrete applications tied to specific industries. These are often small firms lacking a largescale sales operation and eager to grow. As a result, many are beginning to experiment with indirect channel partners to grow their footprint and penetrate various customers segments.

All respondents in CompTIA’s 7th State of the Channel study reported at least some vertical industry work within their business, with three quarters describing that work as important. Of that 75%, 4 in 10 deemed their vertical business as very important, which is a critical distinction. It is most likely this group that has made a concerted effort to make one or more vertical industries a strategic focus and a significant source of revenue. It’s important to note that many respondents that report doing vertical work may only be selling horizontal infrastructure solutions to a cluster of customers in the same industry. This is not the same as becoming an expert in the applications and business processes that an individual vertical such as retail requires. That level of expertise is what truly comprises vertical industry focus and is what many ISVs, vendors and customers are seeking in their channel partners.

It needs noting that vertical specialization is not the simplest path to pursue successfully. Breaking into a specific industry, mastering the vernacular along with niche applications and processes takes time and investment. It’s no wonder that 64% of channel firms said technical specialization is a higher priority for them than vertical specialization (36%). Technical acumen is the comfort zone for the channel after all. But vertical success is a path to profitability, one that depends heavily on acquiring specific business consulting skills as well as applications’ acumen.

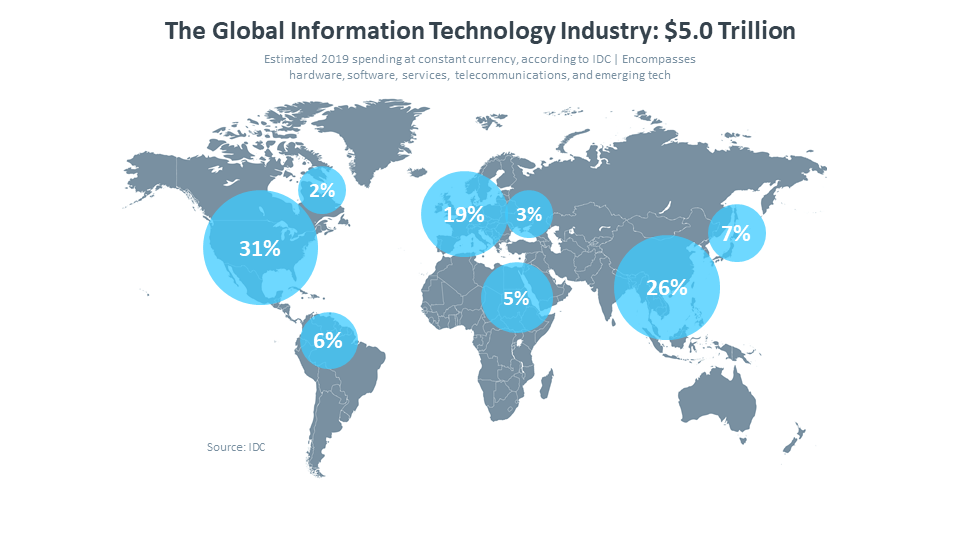

The global information technology industry is on pace to reach $5 trillion in 2019, according to the research consultancy IDC. The enormity of the industry is a function of many of the trends discussed in this report. Economies, jobs, and personal lives are becoming more digital, more connected, and increasingly, more automated. Waves of innovation build over time, powering the technology growth engine that appears to be on the cusp of another major leap forward.

The United States is the largest tech market in the world, representing 31% of the total, or approximately $1.6 trillion for 2019. In the U.S., as well as in many other countries, the tech sector accounts for a significant portion of economic activity. CompTIA’s Cyberstates report reveals the economic impact of the U.S. tech sector, measured as a percentage of gross domestic product, exceeding that of most other industries, including notable sectors such as retail, construction, and transportation.

Despite the size of the U.S. market, the majority of technology spending (69%) occurs beyond its borders. Spending is often correlated with factors such as population, GDP, and market maturity.

Among global regions, Asia-Pacific is the largest, accounting for approximately one of every three technology dollars spent worldwide. Many APEC countries enjoy the twofold effect of closing the gap in categories such as IT infrastructure, software, and services, along with leadership positions in emerging areas such as robotics. If these patterns hold, APEC will continue to grow its share of the global technology pie at the expense of slower growing markets.

The bulk of technology spending stems from purchases made by corporate or government entities. A smaller portion comes from household spending, including home-based businesses. With the blurring of work and personal life, especially in the small business space, along with the shadow IT phenomenon, it can be difficult to precisely classify certain types of technology purchases as being solely business or solely consumer.

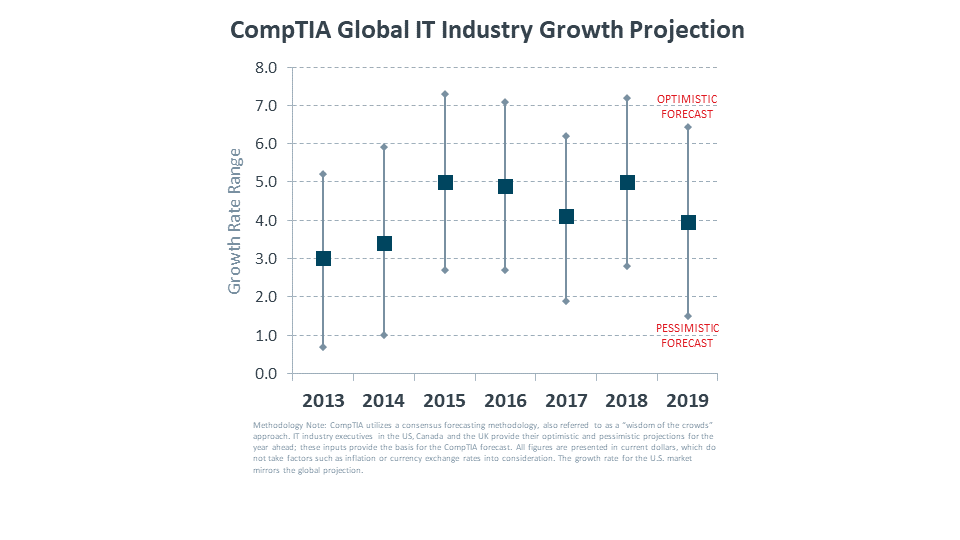

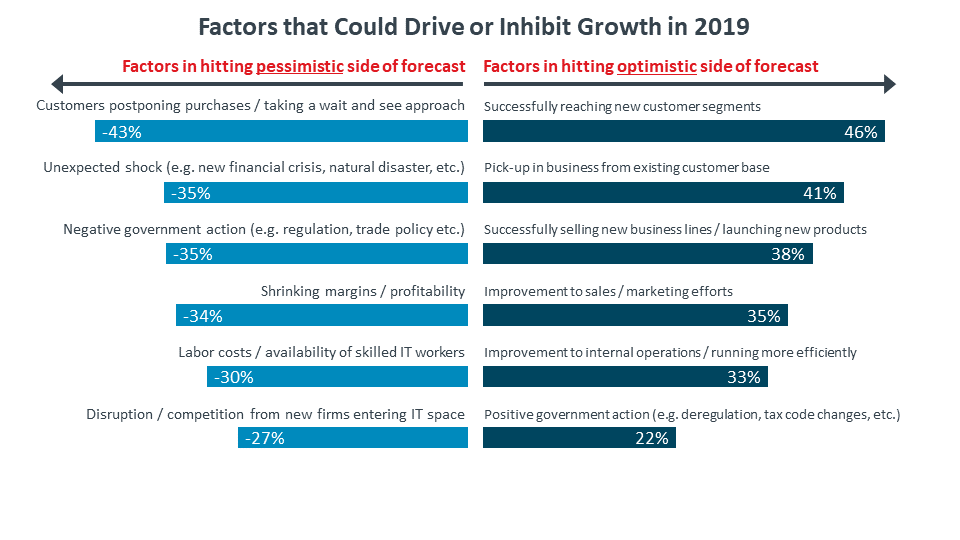

CompTIA projects the global information technology industry will grow at a rate of 4.0% in 2019. The optimistic upside forecast is in the 6.4% range, with a downside floor of 1.5%. This is a broader forecast range than what has been seen in the past couple of years, meaning industry executives see the possibility of more extreme divergence in growth scenarios. To the upside, if customer-buying patterns for core tech products and services maintain, and spending on emerging tech accelerates, growth of 6% or more is attainable. Conversely, a global slowdown in demand, or any slowdown in the adoption of emerging technologies could dampen growth enough to push it towards the 1.5% pessimistic side.

Growth expectations for the U.S. market are in line with the global projection. As the largest tech market in the world, U.S. forecasts and global forecasts are inextricably linked.

CompTIA uses a consensus forecasting approach. This “wisdom of the crowds” model attempts to balance the opinions of large IT firms with small IT firms, as well as optimistic opinions with pessimistic opinions. The results attempt a best-fit forecast that reflects the sentiment of industry executives.

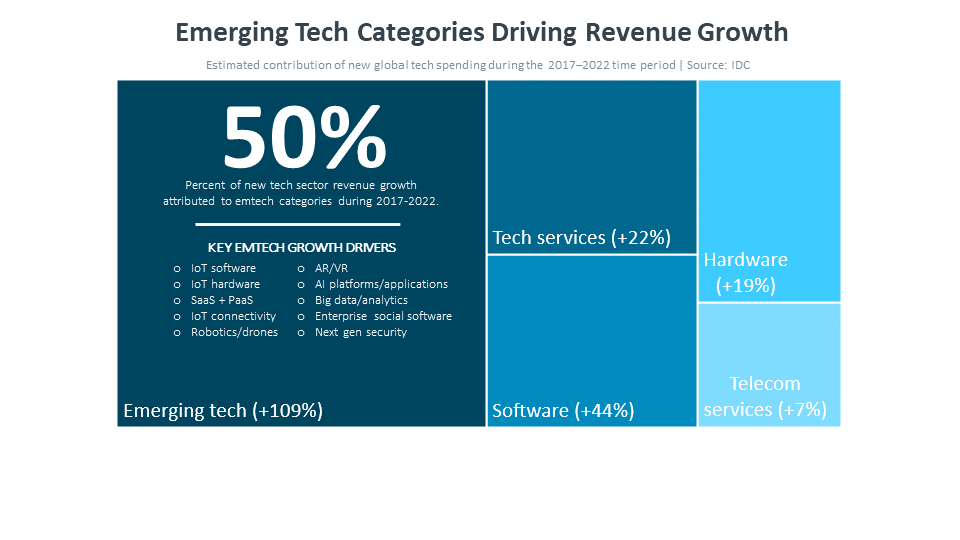

Other factors that influence revenue growth projections include currency effects, pricing, and product mix. The tech space is somewhat unique in that prices tend to fall, which may result in large numbers of units shipped, but modest revenue growth. In the year ahead, the product mix will be an especially important factor, as the high growth rates of emerging categories are expected to more than offset the slow growth mature categories.

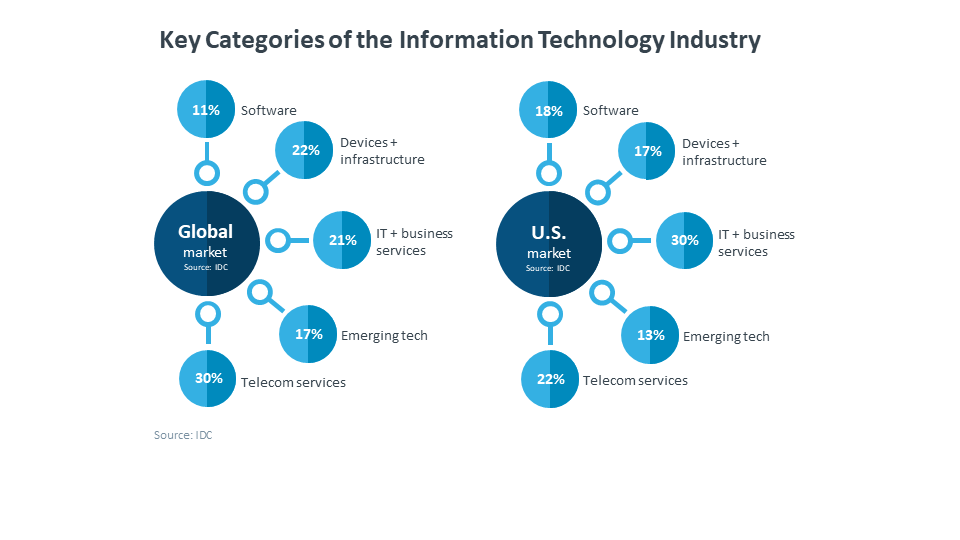

There are a number of taxonomies for depicting the information technology space. Using the conventional approach, the industry market can be categorized into five top level buckets. The traditional categories of hardware, software and services account for 53% of the global total. The other core category, telecom services, accounts for 30%. The remaining 17% covers various emerging technologies that either don’t fit into one of the traditional buckets or span multiple categories, which is the case for many emerging ‘as-a-service’ solutions that include elements of hardware, software, and service, such as IoT, drones, and many automating technologies.

The allocation of spending will vary from country to country based on a number of factors. In the mature U.S. market, for example, there is robust infrastructure and platforms, a large installed base of users equipped with connected devices, and bandwidth. This paves the way for investments in the software and services that sit on top of this foundation. As noted in trend #1 above, advances in cloud computing, edge, 5G, and other infrastructure technologies, will usher in the next wave of services and software.

Tech services and software account for nearly half of spending in the U.S. technology market; significantly higher than the rate in many other global regions. Countries that are not quite as far along in these areas tend to allocate more spending to traditional hardware and telecom services. Building out infrastructure and developing a broad-based digital workforce does not happen overnight. Scenarios do exist, however, whereby those without legacy infrastructure – and the friction that often comes with transitioning from old to new, allows for an easier path to jump directly to the latest generation of technologies.

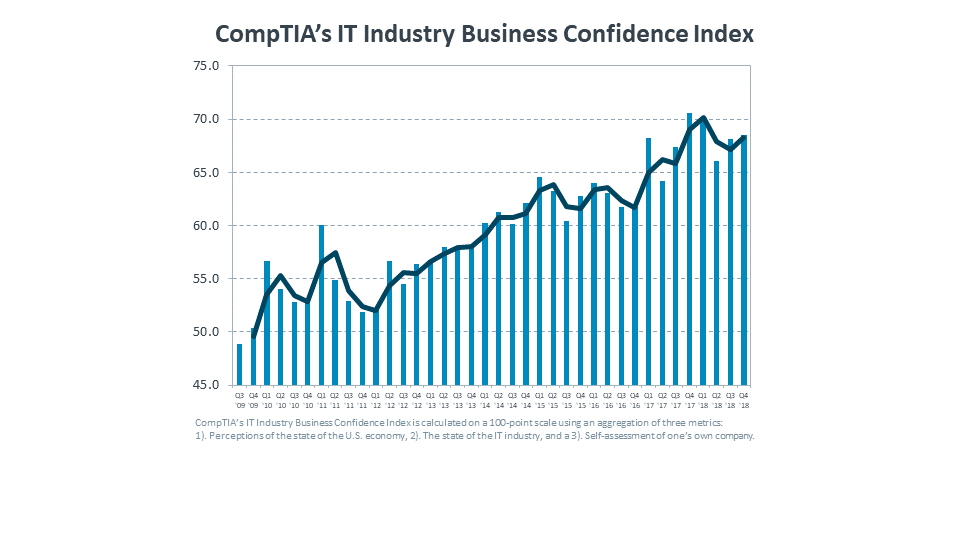

Beyond growth projections, business sentiment is a useful gauge of how industry executives feel about current and future conditions. Despite being off its high, heading into 2019, business confidence among IT industry executives remains well above the long-term average for the index.

The data suggest IT industry business confidence runs counter to other industry sector or consumer indices, many of which dipped during late 2018 and early 2019. This comes as no surprise given the unease stemming from rising debt levels, stock market volatility, international tension, the record-setting government shutdown, Brexit, and any number of other factors.

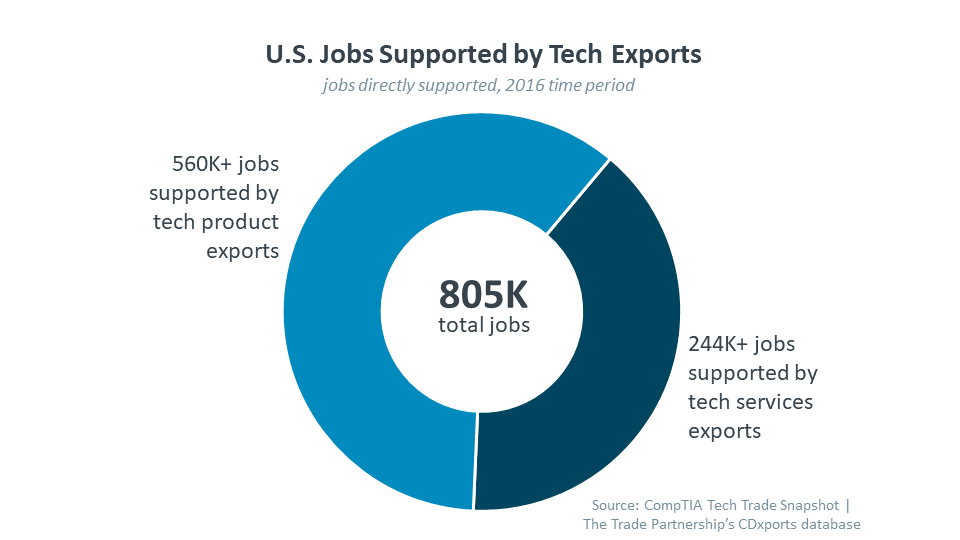

Despite the recent turmoil, international trade remains the backbone of the global technology market. On the production front, a single smartphone may source components from hundreds of suppliers spanning 20 or more countries. Supply chains have never been more global and interconnected. On the consumption front, buyers gravitate toward the best experience, which often encompasses hardware, software, and service ecosystems, wherever they may reside. While convergence continues to be a powerful force in driving users toward similar experiences, the counter weight is the desire for personalization and localization, especially among the always-influential youth market. As such, many countries eagerly import and export technology products and services from trade partners, enjoying the benefits of consumption and economic value creation.

For the most recent year of available data, U.S. exports of tech products and services were an estimated $322 billion, an increase of about 3% over the previous year. Exports account for approximately $1 out of every $4 generated in the U.S. tech industry. For many tech bellwethers, exports account for an even higher percentage of sales, with some generating more than half of their revenue from overseas customers. See CompTIA’s Tech Trade Snapshot for more details.

There may not be a next big thing, but there is one very big thing that is as old as IT itself. Cybersecurity continues to rise in importance as business and daily life are increasingly digitized. Many businesses are increasing their security investments or elevating their security focus, but these actions often follow a defensive approach that utilizes technology tools such as firewalls and antivirus. More and more, firms will realize that they must be proactive in probing for weaknesses or detecting possible breaches. This will involve new skills such as penetration testing, vulnerability assessment, and security analytics. Beyond the technical aspects, organizations will also begin building business processes that enhance security, and they will implement end user training to mitigate human error. There is no doubt that companies are taking security more seriously, but now they must realize that modern security demands a different mentality rather than just more of the same.

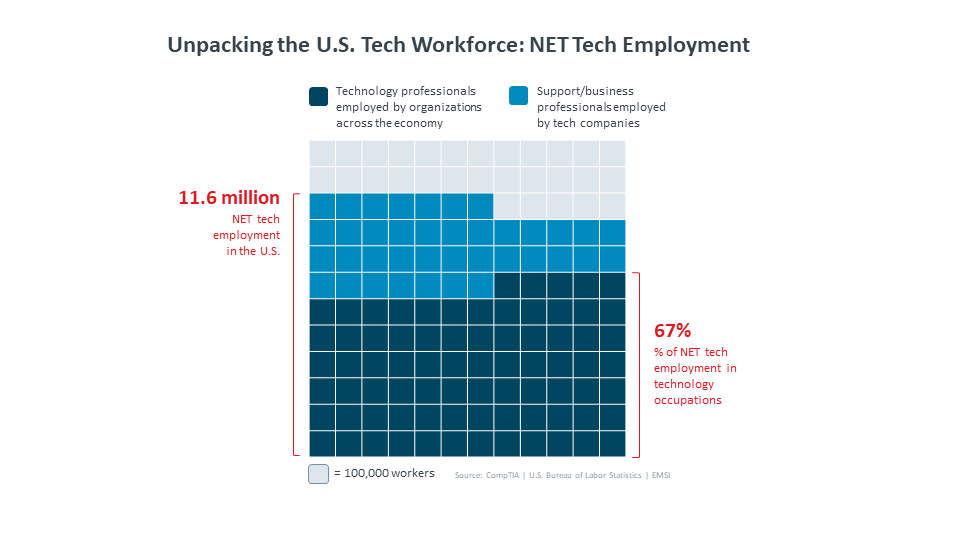

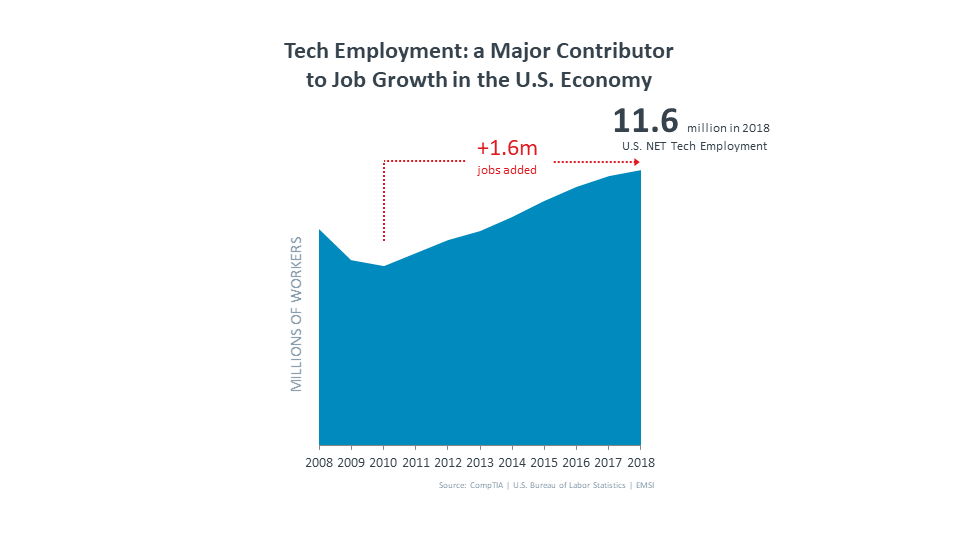

Analysis of the tech workforce begins with an important distinction. Using the classic Venn diagram as a reference point, the tech workforce consists of two separate components, with an area of overlap. Using the ‘net tech employment’ convention depicted in CompTIA’s Cyberstates report, yields a single metric that encompasses both components, making it easier to describe the tech workforce in its entirety.

The foundation is the set of technology professionals working in technical positions, such as IT support, network engineering, software development and related roles. Many of these professionals work for technology companies (44 percent), but many others are employed by organizations across every industry sector in the U.S. economy (56 percent).

The second component consists of the business professionals employed by technology companies. These professionals play an important role in supporting the development and delivery of the technology products and services used throughout the economy. Thirty-four percent of the net tech employment total consists of tech industry business professionals.

One final segment involves workers classified as self-employed. For the purposes of this report, only dedicated, full-time self-employed technology workers are counted towards net tech employment. Workers that are characterized as “gig” workers, which may entail working on the side for supplementary income, are excluded from this analysis due to limitations with the data and to minimize the possibility of double counting.

Relatedly, occupations that use technology – which now extends to large swaths of the labor force, are excluded from CompTIA’s net tech employment definition. The tens of millions of knowledge workers that fall into this category, while certainly important, play a slightly different role compared to those employed by a tech company or working in a technical occupation.

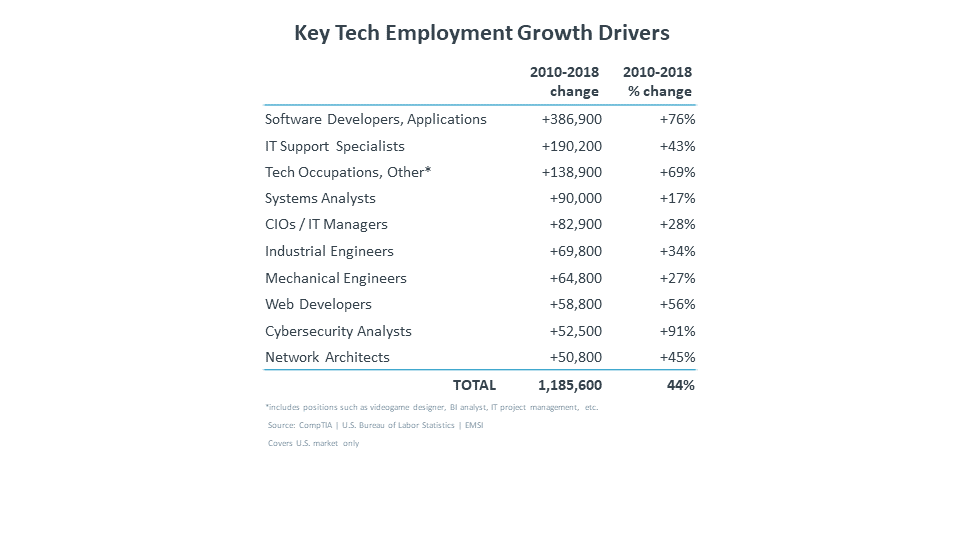

According to CompTIA research, nearly 4 in 10 U.S. tech firms report having job openings and are actively recruiting candidates for technical positions. Another 34% report having openings on the business unit side, such as project managers, market specialists, or sales engineers. Hiring intent is most concentrated among large- and medium-size firms.

Among hiring employers, more than half indicate it is due to expansion, while a similar percentage indicate the need for new skills in areas such as machine learning, IoT integration, or robotics process automation (RPA). These two hiring drivers are clearly intertwined. Firms expanding into new, emerging areas require the requisite skills to proceed with their rollout. Although, it should be acknowledged that expansion may also occur due to a growing customer base in more conventional roles, such as network engineers or IT support specialists employed by an expanding MSP.

Turnover is a natural and healthy component of any industry sector. According to the self-reported data, 43% of tech firms are hiring to backfill departing staff or retirements. During a strong economy with low unemployment and lots of firms hiring, workers tend to feel more confident about testing the market to seek a new opportunity, or perhaps relocate to a desired community.

The Computing Technology Industry Association (CompTIA) is a leading voice and advocate for the $5.0 trillion global information technology ecosystem; and the more than 50 million industry and tech professionals who design, implement, manage, and safeguard the technology that powers the world’s economy. Through education, training, certifications, advocacy, philanthropy, and market research, CompTIA is the hub for advancing the tech industry and its workforce.

CompTIA’s IT Industry Outlook provides insight into the trends shaping the industry, its workforce, and its business models. Because trends do not occur in a vacuum, the report provides context through market sizing, workforce sizing, and other references to supporting data. The interrelated nature of technology – where elements of infrastructure, software, data and services come together, means trends tend to unfold in a step-like manner. A breakthrough may lead to a notable advance, which may then be followed by what could be perceived as lateral movement as the other inputs catch-up. Some of the trends highlighted in this report focus on an early stage facet of a trend, while others recognize a trend moving beyond “buzzword” to reaching a certain stage of market-ready maturity. As such, the timing of trend impact may vary from reader to reader depending on company type, role, or country. Lastly, if it appears a noteworthy technology, workforce, or business of technology trend is missing, it may be because the trend was covered in a previous release of the Industry Outlook. Visit www.CompTIA.org for past reports and an extensive library of research and educational content.

Read more about IT Workforce, The Business of Technology.